The wax seal of St. Peter’s Priory, Thurgarton showing a seated figure holding a key.

On Friday 14th June 1538, the chapter house of the Augustinian Priory of St. Peter in Thurgarton witnessed a very public and stage-managed ceremony, the surrender of the priory to the crown (1) . One can picture the scene.

On Friday 14th June 1538, the chapter house of the Augustinian Priory of St. Peter in Thurgarton witnessed a very public and stage-managed ceremony, the surrender of the priory to the crown (1) . One can picture the scene.

On one side the Prior, John Berwick, and his eight fellow canons gathered together for the last time. The chapter house was the room where they and previous generations of canons had regularly met to discuss Priory affairs but on this Friday there was only one item on the agenda – the dissolution of their house.

Dominating the room stood Dr. Thomas Legh and William Freman, commissioners appointed by Thomas Cromwell to enforce the surrender of the monasteries. They travelled with a retinue of clerks and servants, some probably armed to suppress any dissent.

A third group present to witness the surrender included prominent members of local society: Thomas Markam, knight; Henry and James Hurley; and John Catcher. Also present were “many others” who may well have included local villagers and lay brothers of the priory, curious and anxious to learn of their fate under the new regime.

The document of surrender was probably read aloud and all would have heard that the Prior and his canons acknowledged King Henry’s supremacy in the church and unanimously and voluntarily transferred the priory with all its lands, property and rights to the king in perpetuity.

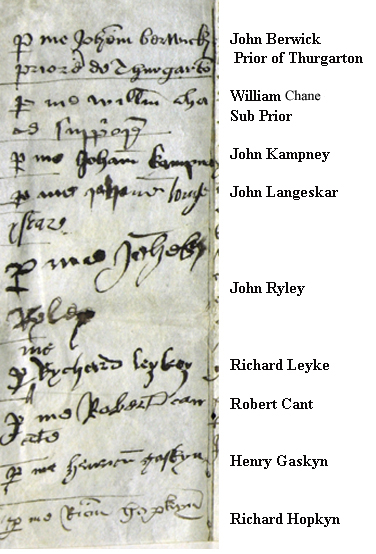

Document of Surrender of Thurgarton Priory Starting with the prior and then the sub-prior each of the canons signed the surrender document along its left margin. The priory’s seal matrix was then used for the last time. The red wax imprint was fixed to the bottom of the document and the matrix handed over to the commissioners.

Starting with the prior and then the sub-prior each of the canons signed the surrender document along its left margin. The priory’s seal matrix was then used for the last time. The red wax imprint was fixed to the bottom of the document and the matrix handed over to the commissioners.

Close up of signatures of prior and canons.

All the canons received pensions for life from the crown. Prior John Berwick received £40 pa together with Fiskerton Hall with its outbuildings, garden, and tithe of hay from two meadows. William Chane the subprior received £6 13s 4d pa and the other seven canons each received £5 pa.

All the canons received pensions for life from the crown. Prior John Berwick received £40 pa together with Fiskerton Hall with its outbuildings, garden, and tithe of hay from two meadows. William Chane the subprior received £6 13s 4d pa and the other seven canons each received £5 pa.

Thousands of religious men and women now had to adapt to a new life outside the cloister. The less fortunate became vagrants, some took up posts in the new Church of England and others lived on their pensions. Numerous pensioners sold their pension rights and by the late 1540s county commissioners were appointed to sort out the chaotic pension scheme. Richard Hopkyn and Henry Gaskyn, whose signatures appear at the bottom of the surrender document (see above), complained that their pensions were in arrears and Hopkyn had purchased Robert Cant’s pension for £13 6s 8d.

So ended over 300 years of the religious life in Thurgarton.

The Wider Scene

The suppression of the monasteries was driven by new reforming ideas in religion, by Henry VIII’s need for a son and by the ever burgeoning royal expenses.

In the early 1530s many Englishmen accepted the need for modest church reform but the vast majority held firmly to their old traditional Catholic beliefs. More radical ideas from Europe were gathering support in England where reformers were especially critical of the great wealth, secular power and supposed immorality of the monasteries.

The rich monastic orders were an obvious target for Thomas Cromwell’s money raising schemes. Ever the efficient administrator he organised a complete survey of church property together with an inquiry into the moral standards of each house. Cromwell’s commissioners included the dreaded trio of Legh, Layton and London; they travelled throughout England and Wales and condemned virtually every house as dens of sexual depravity and immorality. Dr Thomas Legh was so unpleasant that even his fellow commissioners complained of his offensive behaviour. Thurgarton was inspected in 1536 by commissioners Legh and Layton, who reported that “ten brothers were guilty of unnatural offences, the prior had been incontinent with several woman and six others with both married and unmarried women and that eight canons desired to be released from their vows” (3).

Individual monks may well have lapsed but such crude exaggerations were part of Cromwell’s anti-monastic propaganda campaign. Cromwell’s detailed inventory enabled him to prevent the houses from hiding or selling off any valuable items. It also identified those Abbotts and Priors who might prove difficult and should be ‘persuaded’ to resign. The “incontinent prior” of Thurgarton in the 1536 survey was Thomas Dethicke who resigned soon after – he was rapidly replaced by his sub-prior, John Berwick who surrendered the house 16 months later; the generosity of his pension strongly suggests that he was more than cooperative with Cromwell’s commissioners (4).

The break from Rome and papal authority was precipitated by Henry’s need for a legitimate male heir and hence his divorce from Katherine and marriage to Ann Boleyn. In November 1534 The Act of Supremacy and the Treason Act declared Henry VIII to be Supreme Head of the Church and anyone denying his claim was guilty of treason.

In March 1536 parliament passed an act for the dissolution of all religious houses with an annual income of less than £200. The suppression of the smaller monasteries provoked a great northern rebellion, the Pilgrimage of Grace. Forty thousand men led by the unlikely figure of lawyer, Robert Aske, demanded the removal of the evil councillors who surrounded the king (especially Cromwell and Cranmer) and the restoration of their traditional religion. The crushing of the northern rebels in 1537 was the end of any organised resistance and appears to have spurred Henry and Cromwell on to an even more aggressive phase of suppression.

The larger monasteries were now targeted, without any consultation with Parliament; Cromwell and his commissioners simply used the time honoured method of the enforcer- the monks were made an offer they could not refuse. Those who voluntarily transferred all lands and property to the crown would receive a pension for life and those who resisted were traitors; the canons of Thurgarton were faced with this stark choice of quiet acquiescence and a state pension or resistance leading to a traitor’s grisly end. Only a few months earlier the Prior, two monks and four lay brothers of Lenton Abbey in Nottingham were executed for dissent.

Not surprisingly the vast majority of religious houses surrendered voluntarily and so Cromwell engineered the largest peacetime land grab in British history.

Dividing the Spoils

An army of workmen and clerks, controlled by Cromwell’s Court of Augmentation systematically plundered the religious houses. Chapels and shrines were stripped of their valuables. Lead from the roof, timbers, masonry and even nails were recycled and sold; monastic sites came to resemble reclamation yards. Thurgarton’s many chapels and its shrine to St Ethelburga would certainly have suffered the same fate but the fabric of the buildings may have been preserved for the new owner.

Anxiously awaiting events was a rich Londoner, one William Cowper. On 5th June, nine days before the Priory’s surrender, he had written to Wriothesley (Cromwell’s right hand man) that he planned to go into Nottingham for “ the kings surveyors will be there and I am in haste preparing for them for Thurgarton”

The king’s surveyors or commissioners, Legh and Freman, had set out from Halesowen on the 12th June, probably arriving at Thurgarton late on the 13th where with minimum delay they received its surrender on the following day. On the 16th June, Dr Legh wrote from the “late priory of Thurgarton” to Wriothsley “I have received your letter at Thurgarton concerning Cow(o)per and accomplished the effect thereof”. It seems probable that William Cowper was present at Thurgarton around the time of its surrender when he had agreed terms with Legh for the purchase of the priory.

Cowper’s haste may be explained by his knowledge that there were other interested parties. Anthony Birks of Lye, Kent had hopes of acquiring Thurgarton; on 19th August 1538 he wrote to Wriothsley “I beg favour to my Lord Privy Seal (Cromwell) that so many houses of friars being now in suppressing he may help me to one of them as it standeth. The signed bill which the King gave me for Thurgarton Abbey came to no effect as you know”.

On 15th March 1539 the formal contract of sale of Thurgarton Priory was verified. The priory buildings and land in the north of the parish were sold to William and Cecilia Cowper for £510 6s 8d plus the remainder of the 30 year lease which they held on the manor of Ewell and the rectory of Nonsuch in the county of Surrey. One of King Henry’s great projects at this time involved the acquisition of a large expanse of land in Ewell and the surrounding parishes to create the magnificent new royal hunting park and palace at Nonsuch. The Cowpers’ leasehold in Ewell and Nonsuch, lands which were central to the king’s plans, probably clinched the deal (5).

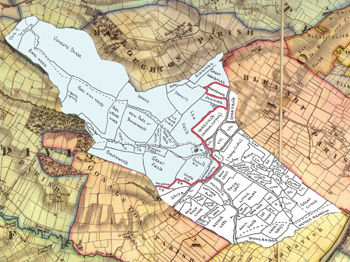

Not all of Thurgarton went to the Cowpers; the village and the southern half of the parish were donated in the 1540s to Henry’s great foundation, Trinity College Cambridge, along with the rectory and living of Thurgarton. The Cowpers leased the college lands in Thurgarton and over the following three centuries there were frequent disputes between the Cowper family and Trinity College regarding land ownership, tithes and rights to timber(6).

Thurgarton parish 1730s– Cowper land in blue and Trinity College land in white

Thurgarton Priory, founded c 1130 underwent a major rebuilding in the early English style in c 1230 and the new church was said to have rivalled Southwell Minster in scale and magnificence. The picture below is an attempt to reconstruct the west front of the new Priory.

Thurgarton Priory, founded c 1130 underwent a major rebuilding in the early English style in c 1230 and the new church was said to have rivalled Southwell Minster in scale and magnificence. The picture below is an attempt to reconstruct the west front of the new Priory.

Reconstruction of West Front of Thurgarton Priory

After the surrender the priory church continued as a parish church but most of it was dismantled and reduced to a single short nave; only part of the west front was preserved together with the northwest tower. Of the secular buildings the kitchen survived as did the ground floor of the west range on which the Cowpers built a new Tudor mansion seen in Buck’s print below.

Buck’s print of Thurgarton Hall 1726

In 1770 the Tudor house and kitchen were demolished to make way for the present brick mansion and in 1854 the church which was “in a very poor state” was restored by the Nottingham architect T. C. Hine who added a north aisle and chancel to the old parish church.

Thurgarton today- parish church and Georgian house

Throughout England and Wales a new class of men built their grand houses on the ruins of demolished monasteries. Some like William Cowper were wealthy city merchants who aspired to the life of their social betters – the landed aristocracy. Within one generation almost a third of English land changed hands and that backbone of English county society was born – the landowning Anglican gentleman.

Throughout England and Wales a new class of men built their grand houses on the ruins of demolished monasteries. Some like William Cowper were wealthy city merchants who aspired to the life of their social betters – the landed aristocracy. Within one generation almost a third of English land changed hands and that backbone of English county society was born – the landowning Anglican gentleman.

References

(1) National Archives, E 372/241 , Surrender of Thurgarton Priory 1538

(2) http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=40083

(3) http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=40092

(4) Trevor Foulds, The Thurgarton Cartulary (Stamford 1994 ) p.ccvi

(5) Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic. Henry VIII, J Gairdiner (Ed.) Vol.13, Parts 1 and 2, June and August 1538.

(6) Trinity College Archives, Box 37 (on Thurgarton)

Very interesting – the reconstruction looks great.

A very interesting and comprehensive account of the surrender of

the Priory !